|

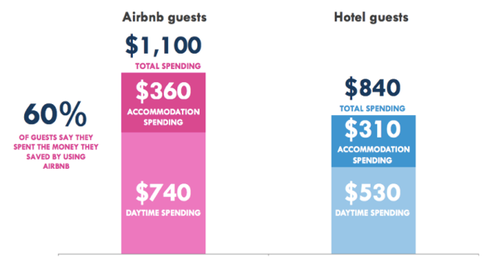

Airbnb is our David, an innovator and facilitator of low-cost travel options and diverse journeying experiences. Large corporate hotel chains are our Goliath, multi-national legends in providing a wide-range of home-away-from-home price points from motels to five-star resorts. Contrary to the Biblical allusion (and major news outlets[1][2]), David will not topple Goliath in the minds of consumers or investors.  Since Airbnb’s founding in 2008, the site allows users to “rent unique places to stay from local hosts in 190+ countries,” [3] it has made the biggest wave in the hospitality ocean since the inception of internet booking agents in the early 2000s. But, while outlets like CNN and Forbes predict that Airbnb’s rapid revenue rise and near-immediate global expansion can beat competitors like Marriott and Holiday Inn, there is just as much evidence to suggest the contrary. In 2009, the aftershocks following the financial crisis created lending freezes, housing starts dived, and the hotel industry’s development of new hotels and rooms dried up. Airbnb saw an opportunity and took it, now valued at $25.5 billion following a $1.5 billion funding round [4]. But, in the last 12 months, hotels have increased construction of new rooms by 21% [5]. This is due to simple supply and demand - the hotel industry has had a slow rebound and every year since 2009 has seen an increase the room rates and the revenue per room. So what gives? Why isn’t the new flashy Airbnb taking down the outdated hospitality market share? Airbnb states that it serves a distinctly different market than hotels, the only overlap being leisure travelers whose demand is variable. According to various economic reports on Airbnb, roughly 70-80% of its listings are located outside of a city’s central hotel and tourist district. It’s no secret that staying merely blocks away from major metropolitan areas can create cost savings. In New York, room rates begin at $588/night when staying at The Chatwal in Midtown Manhattan. A similar location, provided by Airbnb begins at $190/night for a private room.[6] But, is utilizing Airbnb really that cost effective for its users? The above infographic, provided by Airbnb, shows that despite advertisements to the contrary, Airbnb customers spend more per night ($50 more) than hotel guests. However, Airbnb users tend to stimulate local economies more by spending their money elsewhere during the day, something hotel guests do too, just $200 less per day, on average. Plus, following consumer insight gathering, Airbnb claims that a majority of savings from obtaining rooms through their site are being pumped back into the economy by guests during their vacations. When first looking at these metrics, you might be thinking “it’s New York, there’s so much to do, of course people will spend their extra money there.” However, similar statistics have been found for people staying in places all around the country. In San Francisco, guests are staying an average of 1-2 nights more and spending around $300 more throughout their stay than the average hotel guest [7]. Major hotel chains like Hilton are starting to see exactly how Airbnb is disrupting the traditional hospitality industry. Airbnb is averaging 22% more guests per night than Hilton has worldwide and has been valued at a price of $4 billion more than Marriott International [8]. The problem is that once consumers become conscious of the extra money they are spending, they will begin to change their habits. Or, as is the case with 509 1-star reviews (out of 866 total reviews) on consumer ratings site, TrustPilot.com, some consumers won’t be going back due to customer service problems encountered while using Airbnb [9]. While selection biases are common with self-reporting customer review sites, Airbnb’s system of reviews has been called into question [10]. The site has very few poor reviews for all of their available properties, a suspect finding, says Molly Mulshine of Business Insider. After finding several positive reviews for a Californian two-bedroom apartment, she describes her experience as follows: “imagine my surprise, then, when I arrived at the apartment and it was cluttered, dark, stuffy, and not nearly as welcoming as it had looked in the photos.” This is an experience shared by many users, which considering the emphasis AirBnb places on trust [11], this is raises serious questions to the validity of Airbnb’s business model. Airbnb and Uber have both adopted a sharing economy model. Uber has made headlines recently with executives threatening journalists [12] and a driver attacking a passenger with a hammer [13]. But, these issues have less to do with Uber as a company and more to do with a business model that unloads responsibilities onto its customers. Airbnb saves millions in costs by not owning or operating any properties, something made clear in their terms of service. Their business is a cash cow: collect money for a rental matching service while facing none of the usual hospitality operating costs. Airbnb’s margins are enormous because they only deliver a website and the occasional refund of rental fees due to a bad user experience. While nothing is wrong with this system, larger companies (like Airbnb’s accommodations competitors) with massive amounts of physical capital can have millions in taxes collected on them, Marriott alone paid $64 million in taxes in 2014 [14]. In addition to taxes, regulations and the enforcement of employment laws are essential to growing a stable economy, a practice not easily accomplished in this new “shared economy.” A handful of cities are collecting taxes from Airbnb, a company that leaves it to hosts to abide by tax laws. From employment to Social Security to disability, Airbnb’s vast array of financial resources are not being spent to further the “greater good,” and they have relinquished all responsibility of what happens to consumers once they rent. Speaking of the greater good, in a global analysis of income inequality from 55 countries from 1960 to 2006, University of Michigan’s Gerald Davis found that the higher the proportion of employees working in large companies, the lower the income inequality [15]. The hotel industry is a great example of how internal labor markets reduce wage variation more than a traditional market arrangement. David is growing, tech savvy and leaves the responsibility of maintaining facilities and taking care of customers to larger companies, like Goliath. While there’s no question that Airbnb’s success has been sustained and created a multi-billion dollar phenomenon, but is it a viable plan in the long-term? Can Airbnb avoid the intense scrutiny of Uber? Will Airbnb merge the gap between their shared economy and the heavy regulation of the hotel industry? Only time can answer these questions, but it looks like Airbnb’s David is missing the slingshot that made him once victorious.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |